Meredith L Weiss

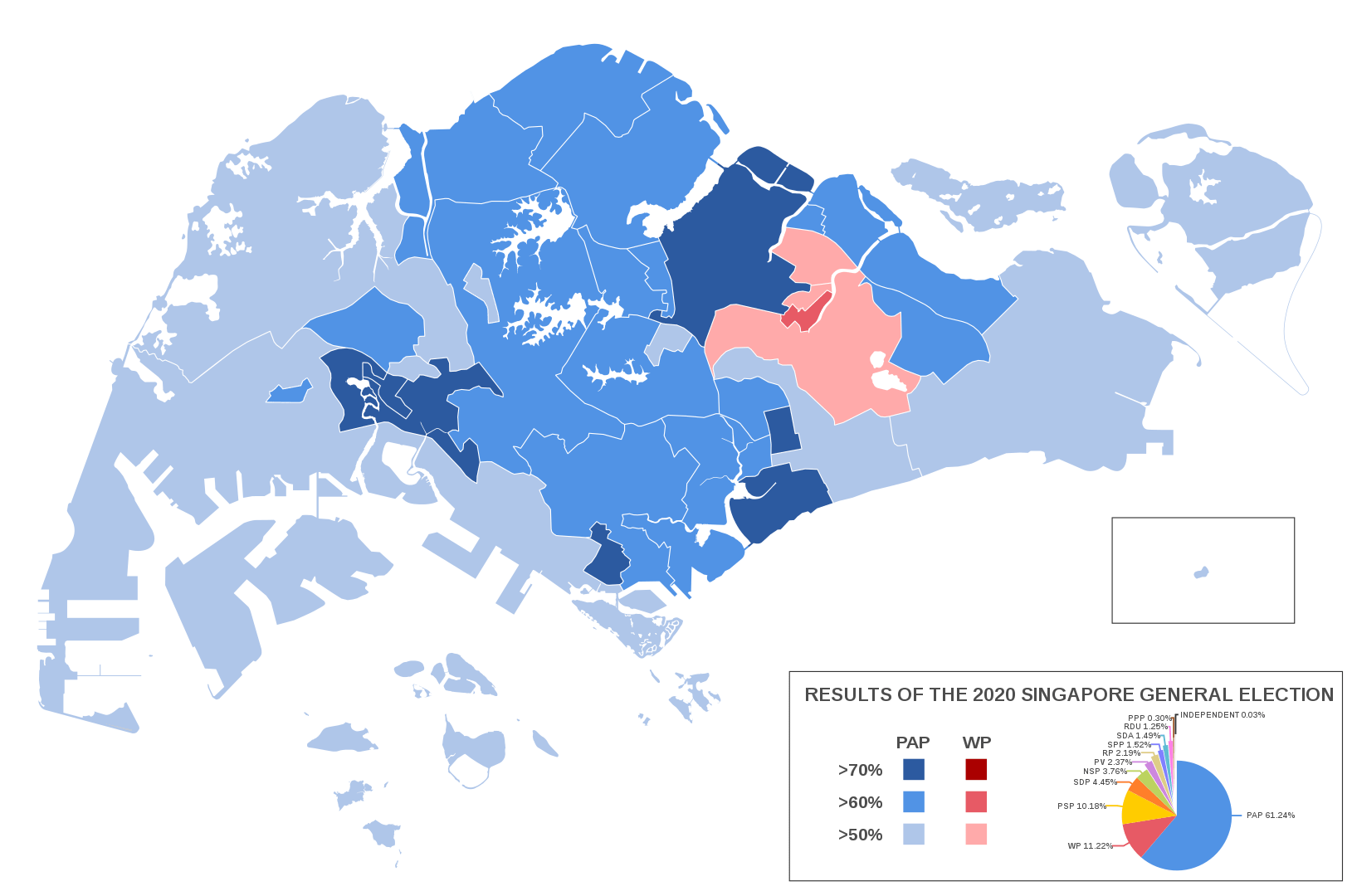

While these results might seem decidedly underwhelming elsewhere, by Singapore standards, they are quite significant. It is not just that the People’s Action Party’s (PAP) margins declined – from just under 70 percent of the popular vote in 2015 to 61.2 percent now, their third-worse showing to date (and only narrowly higher than those tallies: 60.1% in 2011; 61.0% in 1991) – but also that so many observers (and politicians) predicted precisely the opposite. For the opposition to be wiped out, losing the 6 seats it held previously, was entirely plausible; instead, they now hold a record 10 seats. (Two more opposition “top losers” may now enter Parliament as non-constituency MPs.) Moreover, while only the Workers’ Party (WP) won seats (again), two other opposition parties, the new Progress Singapore Party (helmed by an 80-year old ex-PAP stalwart) and the long-standing Singapore Democratic Party, came close.

Arguably more important than the actual seat distribution, though, are the patterns we see emerging. The structure of Singapore’s electorate makes it exceptionally difficult for changes in voter sentiment, strong feelings for or against a specific candidate, or even specific policy preferences to translate into electoral wins and losses. But we do see broad patterns in the fact that, with good reason to expect a “flight to safety” in these mid-pandemic elections, we instead saw a strong protest vote, nearly nation-wide.

Map of the results of the Singaporean general election 2020. Image: Seloloving, Wikipedia Commons

Unfazed by PAP high-handedness

Moreover, critical voices were especially obvious among youth (and reducing the voting age from 21 to 18 featured on opposition platforms, making those youth voices all the more noteworthy). It matters that the breakthrough WP team is so obviously young – a personable mix of wonks and activists, unfazed by the PAP high-handedness; the PAP came off repeatedly as somewhere between smugly elitist and bullying. That impression surely reinforced the WP’s appeal to give the PAP only a mandate, not a blank check. The candidates who caught the spotlight, especially among the opposition, are neither all Chinese nor all male. Indeed, a kerfuffle over a young Malay WP candidate’s past social-media commentary on racial and religious discrimination in Singapore – in the context of the global reverberations of Black Lives Matter, as well as the known reality of Singapore’s own ethnic dynamics – suggested that many Singaporeans (especially those lacking Chinese privilege) would prefer to acknowledge and confront, rather than doggedly ignore, issues of race and inequality. (At the same time, several opposition platforms foregrounded a xenophobic streak, however much framed in terms of anxiety over competition for well-paying jobs.)

Logo for Workers’ Party of Singapore.

Clearly, a substantial share of the population wants debate, consideration of alternatives, and a shift from the conceit of “apolitical” technocratic management. The WP acknowledges that its platform is not far removed from the PAP’s, but it does lean differently – and as one of their new stars explained compellingly in a debate, that half-step left does matter in terms of priorities and whose interests take precedence. Even mere fine-tuning of policies on housing, pension funds, wage policies, and the like could be highly consequential, given the scope of the state’s role in all these domains. Nor did the PAP succeed in making the election a fully “local” one, about which candidate or team (given Singapore’s mix of single- and multi-member constituencies) can best manage housing estates: the leading opposition parties all sustained a refrain of accountability, transparency, and stronger democracy – even as they also touted, since they must, their commitment to walk the ground and problem-solve diligently.

Intriguing questions ahead

Perhaps most intriguing in the near term is the question of leadership. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has indicated that he will steer Singapore through the COVID-19 crisis before stepping down, yet his designated successor, Heng Swee Keat, hardly shone; indeed, the GRC team he helmed barely squeaked out a win. (As others have rightly noted, it could also well be that the team would have sunk had the party *not* shifted him there.) While again, one cannot read sentiment toward any given candidate too neatly off a bloc-vote outcome, this result cannot be read as a strong vote of confidence in the “4G” leaders. All told, Singaporean voters do not seem to think the PAP has all the answers. That’s hardly unusual – but it’s at odds with the PAP’s usual way of approaching the business of policymaking: their argument for decades, including throughout this campaign, has been precisely that only they have the best ideas. We’re unlikely to see a sharp turn toward open parliamentary debate, but the PAP could well take this message that a significant share of voters do want more voices heard to heart, especially as it confronts the very rocky economic shoals ahead.

Meredith L. Weiss is Professor of Political Science in the Rockefeller College of Public Affairs & Policy at the University at Albany, State University of New York. She is author of Student Activism in Malaysia and Protest and Possibilities.

Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect FORSEA’s editorial stance.